On route from hell on earth to the gift of the gods – post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

© Jorgan Harris.

1. What is Post-traumatic stress disorder?

Post-traumatic stress is also known as shell shock, battle fatigue, accident neurosis and post-rape syndrome.

Post-traumatic stress disorder causes distress and interference in daily life. PTSD is a debilitating condition, which follows a traumatic event. Often, people with PTSD are plagued by persistent frightening memories of the traumatic event, which sets off the condition or feel emotionally numbed by the ordeal.

2. Who is affected by Post-traumatic stress disorder?

It is estimated that up to ten percent of the population have been affected by PTSD. It was once thought to be mostly a disorder of war veterans. PTSD can however affect anyone who has been involved in a significant traumatic event.

3. What are the symptoms of PTSD?

Symptoms of PTSD normally only appear within three months after the trauma. However, sometimes the condition can appear months, even years after the traumatic experience.

The symptoms of a Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder as described by the DSM 5 are:

Note: The following criteria apply to adults, adolescents and children older than 6 years.

A. Exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury or sexual violence in one (or more) of the following ways:

- Directly experiencing the traumatic event(s).

- Witnessing, in person, the event(s) as it occurred to others.

- Learning that the traumatic event(s) occurred to a close family member or close friend. In cases of actual or threatened death of a family member or friend, the event(s) must have been violent or accidental.

- Experiencing repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of the traumatic event(s) (e.g. first responders collecting human remains; police officers repeatedly exposed to details of child abuse).

Note: Criterion A4 does not apply to exposure through electronic media, television, movies or pictures, unless this exposure is work related.

B. Presence of one (or more) of the following intrusion symptoms associated with the traumatic event(s), beginning after the traumatic event(s) occurred:

- Recurrent, involuntary and intrusive distressing memories of the traumatic event(s).

- Recurrent distressing dreams in which the content and/or effect of the dream are related to the traumatic event(s).

- Dissociative reactions (e.g., flashbacks) in which the individual feels or acts as if the traumatic event(s) were recurring.

- Intense or prolonged psychological distress at exposure to internal or external cues that symbolise or resemble an aspect of the traumatic event(s).

- Marked physiological reactions to internal or external cues that symbolise or resemble an aspect of the traumatic event(s).

C. Persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the traumatic event(s), beginning after the traumatic event(s) occurred, as evidenced by one or both of the following:

- Avoidance of or efforts to avoid distressing memories, thoughts, or feelings about or closely associated with the traumatic event(s).

- Avoidance of or efforts to avoid external reminders (people, places, conversations, activities, objects, situations) that arouse distressing memories, thoughts, or feelings about or closely associated with the traumatic event(s).

D. Negative alterations in cognitions and mood associated with the traumatic event(s), beginning or worsening after the traumatic event(s) occurred, as evidenced by two (or more) of the following:

- Inability to remember an important aspect of the traumatic event(s) (typically due to dissociative amnesia and not to other factors such as head injury, alcohol, or drugs).

- Persistent and exaggerated negative beliefs or expectations about oneself, other, or the world (e.g., “I am bad”, “no one can be trusted,” “the world is completely dangerous,” “my whole nervous system is permanently ruined”).

- Persistent, distorted cognitions about the cause or consequences of the traumatic event(s) that lead the individual to blame himself/herself or others.

- Persistent negative emotional state (e.g., fear, horror, anger, guilt, or shame).

- Markedly diminished interest or participation in significant activities.

- Feelings of detachment or estrangement from others.

- Persistent inability to experience positive emotions (e.g., inability to experience happiness, satisfaction, or loving feelings).

E. Marked alterations in arousal and reactivity associated with the traumatic event(s), beginning or worsening after the traumatic event(s) occurred, as evidenced by two (or more) of the following:

- Irritable behaviour and angry outbursts (with little or no provocation) typically expressed as verbal or physical aggression toward people or objects.

- Hyper vigilance.

- Reckless or self-destructive behaviour.

- Exaggerated startle response.

- Problems with concentration.

- Sleep disturbance (e.g., difficulty falling or staying asleep or restless sleep).

F. Duration of the disturbance (Criteria B, C, D and E) is more than 1 month.

G. The disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

H. The disturbance is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance (e.g., medication, alcohol) or another medical condition.

People suffering from PTSD may re-experience the traumatic event in many ways. They often get sudden, vivid memories, flashbacks or dreams accompanied by painful emotions that take over the victim’s attention. This re-experiencing of the trauma is called a flashback – a recollection so powerful that the individual may feel as if the trauma is actually being experienced all over again. These memories can also be triggered when a person is exposed to cues which may remind him or her of the incident. I am reminded of a client who was a victim of a robbery in a well-known chain group of shops. He was held at gun-point by a man wearing a yellow T-shirt. Every time he saw a shop of the specific group after this incident, or when he saw an advert for the shop and every time he saw a pistol, or when he saw anybody wearing a yellow T-shirt, he went into intense physical and psychological distress as seen in the under mentioned text.

At times, the re-experiencing occurs in nightmares that appear so real that the person wakes up screaming terrified as if the trauma was being re-enacted in sleep. In young children, distressing dreams of the traumatic event evolves into generalised night-mares of monsters, threats to other people and rescue attempts.

The re-experience comes as a sudden, painful onslaught of emotions that seemingly have no cause, but are usually linked to the traumatic event. These emotions, often those of grief that bring tears and tightening of the throat, can also be of anger or fear. In such cases, fantasies of revenge may occur. Individuals recount that these experiences occur repeatedly, in much the same way as memories or dreams of the traumatic event would also occur.

The person will try to avoid these cues at all cost. It also affects a person’s relationships with other people, because he or she will avoid close emotional ties with family, friends and colleagues. Emotions are severely suppressed, many PTSD sufferers will frequently say that they cannot feel emotion, especially towards those closest to them. When emotions are felt, there is often difficulty in expressing them.

PTSD sufferers often void situations that may serve as reminders of the traumatic event because the symptoms may worsen when engaging in an activity or situation, which resembles – even in a very small part – the original trauma. They may experience psychological distress when confronted with any cues that resemble the trauma in the form of anxiety, stress or uncomfortable emotions. They may also experience physical symptoms like sweatiness, palpitations, shaking, nausea etc.

Over time, the person may become so fearful of particular situations that his or her daily life is characterised by attempts to avoid these situations. They sometimes can’t remember important aspects of the trauma and have a reduced participation in meaningful activities.

Sufferers often become irritable and may have trouble concentrating or remembering current information. Insomnia (difficulty sleeping) may develop as a result of the irritability. PTSD sufferers may have exaggerated startle response when exposed to a noise such as a gunshot.

Can you think what will happen if they are repeatedly exposed to these cues? All these symptoms keep on stacking up and the symptoms keep on worsening.

It is clear that people have to be debriefed after a traumatic incident. Unfortunately, this does not always happen. If one keeps in mind that PTSD can be caused not only by a threat to the person’s own life but can also be caused by a threat to the physical integrity of self or others. The more incidents that happen without treatment, the stronger the triggers become and the more difficult it will then be to recover. Studies have shown that people who are debriefed immediately, stand a lessor chance of developing PTSD.

This problem is worsened by the fact that PTSD does not develop immediately after the trauma but can develop after a month, even months or years after the incident. The individual may initially feel as if nothing has happened and indeed shows no symptoms. When the symptoms eventually do appear – the individual may be surprised and not know where it is coming from.

It is really difficult to talk to the sufferer of PTSD about it. As you might have realised, they don’t want to talk about it. The current “therapy” is that Cowboys don’t cry and a glass or two of alcohol will take it away. Some joke about it in the hope that it will be gone by tomorrow but the imprint in the subconscious mind does not go away.

What is really happening here is that we use different defence mechanisms to protect us against those memories. One of the most commonly used defence mechanisms against PTSD is suppression. We are literally placing a huge concrete block on top of our feelings to ensure that it stays suppressed. These suppressed feelings, however, will always push back in the form of trauma, anger and depression. A battle develops now – the anger and the trauma keep on pushing upwards and the defence mechanisms keep on pressing downwards. These counter forces then cause anxiety (or stress). Stress, literally speaking is when there is a pressure from two different directions. Through these painful experiences there is always a threat that it will break through to the surface.

Alcohol allows you to relax and suppresses the anxiety. The use of alcohol is an attempt to get rid of these painful emotions and to forget these painful events. Although loneliness can be suppressed with alcohol it only lasts for a short a while. When a person is under the influence these suppressed emotions of especially anger may come forward. Substance abuse helps to blunt emotions and allows the traumatic event to be temporarily forgotten. A person with PTSD may show poor control over impulses and may, therefore, be at risk for assault or suicide as an attempt to “grab control” again.

Depression, anxiety and social withdrawal may co-exist with PTSD.

It is widely thought, especially by policemen and soldiers, that PTSD only happen to “weak” people. The truth is that PTSD can happen to the bravest of us. A chemical reaction in the brain is the cause and PTSD can happen to anyone, no matter how strong or weak that person is. It is, in this context, almost like cancer. Cancer can happen to the weak elderly but it can also happen to a fit and strong rugby player. PTSD does not discriminate. Children as well as Recce’s can get PTSD.

It is not a sign of weakness to seek help and it is only the strong who have the guts to recognise a problem and to seek help for it.

4. Therapy

Therapy for PTSD can actually be very simple. Using BWRT or hypnosis together with NLP, such a traumatic experience can be desensitised with relative ease. Gone are the days where a person is taken back to the original experience to relive it again. Nowadays it can be done in a “disassociated” manner. The client is being taken back to the traumatic experience where he or she is seeing the event as if on a TV screen or a movie screen, as if the event is happening to somebody else who “happens” to look like them, who “happens” to have had the same experience as them and who “happens” to have shown the same reactions as them. It is however not them. Clients experience minimal trauma during hypnosis and they are actually surprised to realise how easy it is to overcome these symptoms without them having to do anything. You do not have to suffer. It is not necessary to destroy your own life with these ghosts. Get help. It is available. You can be free of all those ghosts.

5. Test yourself – are you suffering from PTSD?

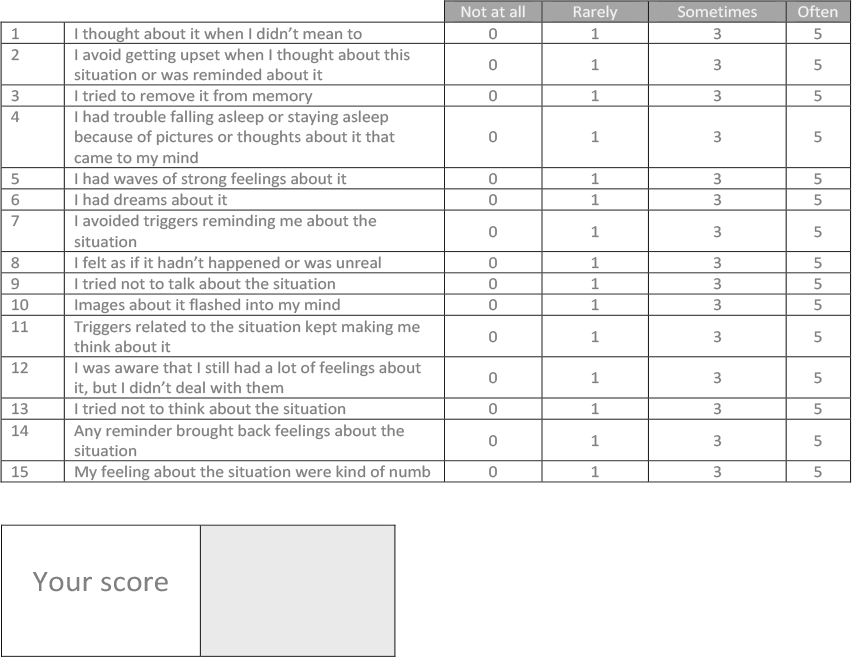

The Impact of Event Scale (IES) is a short set of 15 questions that can measure the amount of distress that you associate with a specific event. The IES was developed in 1979 by Mardi Horowitz, Nancy Wilner and William Alvarez.

The test is often useful in measuring the impact that you experience following a traumatic event. Studies show the IES is valuable in spotting both trauma and less intense forms of stress. It will show how much an impact event is currently bothering you.

Here are the questions and instructions for the Impact of Event Scale.

Below is a list of comments made by people after stressful life events. Please mark each item, indicating how frequently these comments were true for you during the past seven days. If they did not occur during the specified time, please mark the “not at all” column.

Select only one answer per row:

Scoring: Total each column and add together for a total stress score.

For example, every item marked in the “not at all” column is valued at 0. In the “rarely” column, each item is valued at a 1. In the “sometimes” column every item marked has a value of 3 and in the “often” column each item is valued at 5. Add the totals from each of the columns to get the total stress score.

The next section will help you to understand the significance of your score.

What Does My Score on the Impact of Event Scale Mean?

The Impact of Event Scale and the Impact of Event Scale-Revised are useful in measuring how a stressful event may have affected you. For example: on the original 15-item Impact of Event Scale (IES), the scores can range from 0 to 75. You can interpret the IES scores in the following way:

Original Impact of Event Scale (15 questions):

0 – 8 No Meaningful Impact

9 – 25 Impact Event—you may be affected.

26 – 43 Powerful Impact Event—you are certainly affected. You may need to seek therapy.

44 – 75 Severe Impact Event—this is capable of altering your ability to function. It is important to seek therapy.